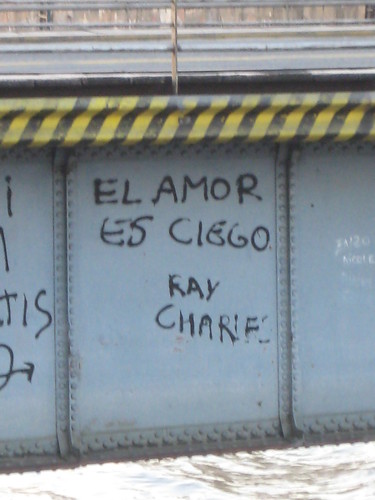

Our travels across this city have revealed the unevenness of its development and, most interestingly, the forgotten, obsolescent, and recrementitious spaces that are left behind as cities embrace "progress." Often, these are the interstitial spaces, the edges of industrial zones or government tenancies, the often trash-strewn spots that are surely owned by someone on paper but of which no one takes ownership. In these spaces, street art often springs up, as cavalier creative types highlight the contradictions of such property that no one cares about until someone else decides to care about it (one can't help but think too, here in Argentina, of the Malvinas/Falklands in these terms).

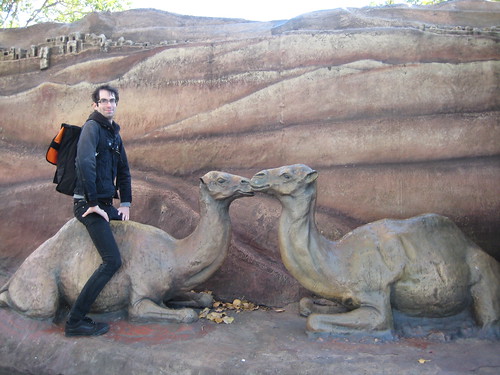

At the edge of an enormous railyard, bounded to the north by the Retiro slum and to the south by high-rise apartments and hotels, we stumbled across a sculpture workshop/theater/arts space called El Gato Viejo. It is full of sculptures cobbled together from industrial detritus, mostly in the shape of old cars, airplanes, and dinosaurs—essentially obsolete and decrepit pieces of iron, tin, and aluminum put together to whimsically represent obsolete or extinct forms that have perennially captured our imagination. El Gato Viejo is anything but neat and orderly, and because our visit occurred during a rainstorm, the mud and puddles were fierce. Although the city has given this alternative arts space permission, it does not come across as a clean, inviting arts exhibit meant for tourists. It's dirty and grimy, lacking in pretense—it's beside railyards, composed of industrial waste, and it doesn't pretend otherwise.

In other areas, grassroots memorials spring up, such as one near the back of the Once train station devoted to the 200 or so jovenes who died in a fire at the Cromañon rock club in 2004, attempting to escape through doors bolted and wired shut by club owners trying to keep fans from sneaking in without paying.

Anyway, this cityscape is fascinating because, unlike New York, Buenos Aires has not (yet) engaged in a wholesale erasure of the past as de rigueur urban planning policy. Though there was certainly slum clearance in decades past (particularly as the highways that traverse the city were built), today gentrification is its more "genteel" heir, displacing working-class residents and neighborhood businesses—plumbers, glass-makers, welders, auto-repair shops, upholsterers, all of those trades that rely on the conservation and repair of old things, rather than their replacement. In Palermo Hollywood, for example, high-rise condos, boutiques, and restaurants catering to foreigners and the "creative class" (manifested here by those working for the many television and movie studios) are rapidly squeezing out what was here before, in this neighborhood of working people once known as Pacifico.

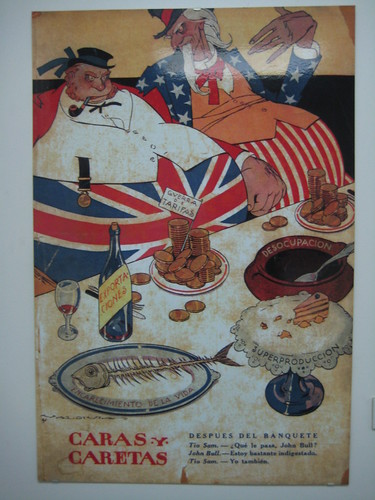

In the neoliberal period, beginning more or less with President Menem, Argentina has embraced models of urban development now seen throughout the world. Inevitably, some spaces have been left behind, and these are the ones that often offer the best insight into the dreams of the past, or the repressed memories of the present, as seen above. Elsewhere in the city, the unevenness of development is not quite as visible by direct juxtaposition; instead, the lack of older, traditional housing and businesses points to a wholly forward-looking neighborhood identity.

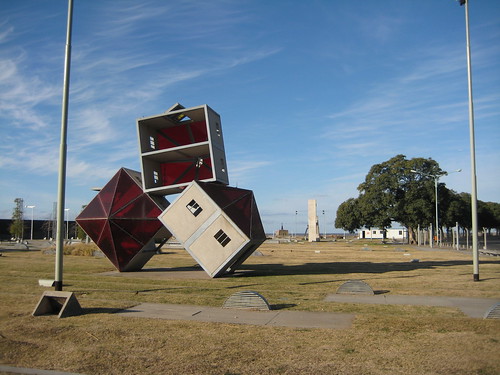

Puerto Madero, which was a fallow port space made obsolescent by container shipping, has become a sort of touristic themepark (themes: "global city," "redevelopment"), with its requisite

Santiago Calatrava bridge next to its requisite Hooters.

As cool as the Calatrava bridge may be, its function is the same as Calatrava bridges worldwide: to symbolize the arrival of neoliberalism. No urban redevelopment, in the post-Guggenheim-Bilbao age, is complete without a signature architectural spectacle, and, in a hundred years, historians will look back and see so many of Calatrava's (and Gehry's) works as period pieces. In this case, the bridge is actually fairly tasteful. That the bridge is functional (ie, movable) is a paean to the memory of Puerto Madero as the center of Buenos Aires' port. Today, Calatrava's bridge rarely needs to open; its function is its aesthetics, its spectacle-commodity-ness. If the city were concerned with using the most up-to-date technology for its movable harbor bridges, the Calatrava wouldn't be a superfluous pedestrian bridge south of the harbor's mouth and the yacht club. (One assumes a pedestrian bridge designed by Calatrava is cheaper than an auto bridge.)

Puerto Madero combines reclaimed grain storage facilities—now turned into lofts and restaurants—as well as a newly constructed museum (not open yet) and many new office and upscale residential buildings, with, ostensibly, the only functional use of these waters: a yacht club. Unlike New York City, which has all but completely turned its back on its past as a major port, Buenos Aires was never the ideal locale for a shipping center due to its geography (and hydrography, I suppose)—and even still, it maintains a large, modern container port just to the north of this tourist destination. Despite the economic rollercoaster of the last 50+ years here, Buenos Aires has managed to maintain what is central, in my opinion, to a healthy working class in a postindustrial era: its port. In this way, the use of old dock cranes as decorations around Puerto Madero doesn't come off as crass or tasteless.

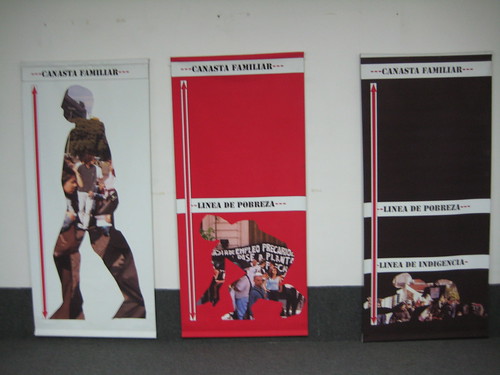

But the idea of starting fresh, in a completely new part of the city, away from the hustle and bustle—and away from the social problems of the older neighborhoods (like poverty!)—is creepy and a bit fascistic. It's clear, however, that activists in this city won't let such an attempt to turn away from reality go unnoticed: in 2006, piquetero leader Raúl Castells opened a small lunch counter here to feed poor youth and elderly people, which was later shuttered by government order.

One imagines that the slogan "We fight for an Argentina where the dogs of the rich do not eat better than the children of the poor," however apposite, didn't sit well with those buying the exclusive condos across the water.

Since its "redevelopment," Puerto Madero has become a haven for speculators. After the economic crisis of 2001, real estate, especially in the form of speculation, has been

the growth industry for two reasons: first, well-heeled Argentines no longer trust the banks as they once did, and real estate offers what seems like a sounder investment; second, overseas clients can purchase real estate of a caliber that might be out of reach at home due to the favorable exchange rate. Thus, Puerto Madero, which was basically a no-go zone at the end of the dictatorship, with disused warehouses and grain silos, is now

the place for foreigners to buy up property. The number of high rises under construction or recently completed there is astounding. And, so, the repurposing of this area mirrors the overall retooling of the global economy under regimes of deindustrialization, financialization, and rampant speculation.

With all that in mind, who needs a pizza and a beer?

You don't want to know what we paid for it.